James Black

58, Male

See sections below for further patient management details...

-

Paroxysmal AF

Mr Black has paroxysmal AF.

Depending on the frequency of episodes and how symptomatic he is, there are options to try to keep him in sinus rhythm or control his heart rate when he has paroxysms of AF. The key risk of having AF is developing a complication.

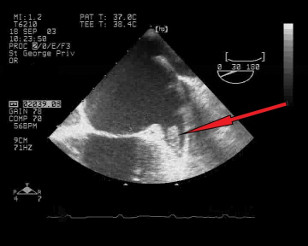

Figure A. Cardiac image: LA appendage with thrombus (arrowed in red)

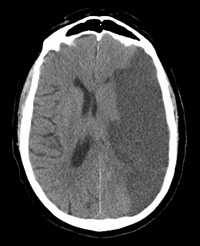

Figure B. Brain image: Large stroke in the left hemisphere as a result of a thromboembolic obstruction from AF In AF the atria do not contract in synchrony but have a disorganised pattern. Blood tends not to flow normally through the atria and can stagnate in certain pockets within the atria. A common area is in the atrial appendage (see Figure A). If this blood clot escapes and enters the circulation it can lodge in one of the end-arterioles in an organ. The brain is particularly vulnerable and ‘emboli’ can shower into the brain causing small or large strokes (see Figure B).

-

Prevention of stroke:

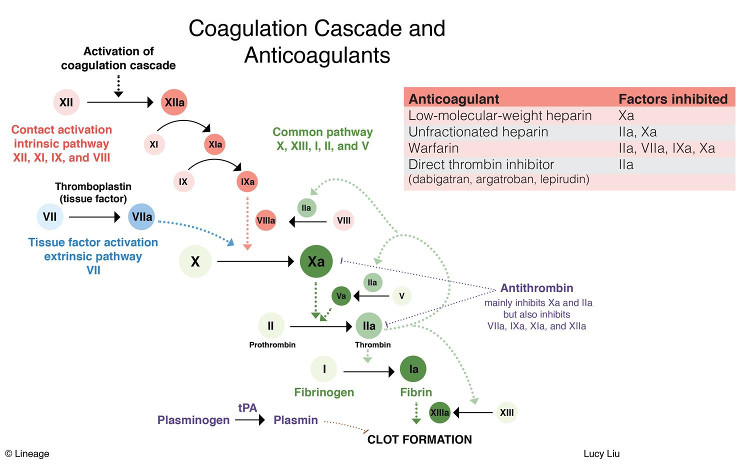

The main aim therefore is to reduce the likelihood of a stroke. In practice, we do this by reducing the clotting ability of the blood so it has less potential to cause a clot. We use drugs that inhibit parts of the clotting cascade (see diagram below).

Coagulation Cascade and Anticoagulants

Source:http://step1.medbullets.com/hematology/111030/anticoagulantsThe drug of choice for many years has been warfarin which inhibits several clotting factors. However this involves frequent blood tests to check it is working. A newer class of agents called novel oral anticoagulants are as good as warfarin for preventing strokes in AF and have less side effects and do not require regular monitoring - Dabigatran inhibits thrombin, whereas rivaroxaban, edoxaban and apixaban all inhibit Factor Xa.

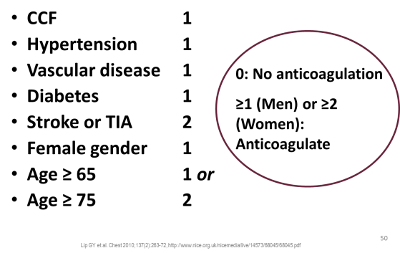

Before starting a patient on an anticoagulant we should work out the risk of someone in AF developing a stroke using a validated scoring system (CHA2DS2VASc). The risk is divided into low, moderate or high depending on the score. Most patients will be started on anticoagulation if they reach moderate risk (score of 1 equating to an annual stroke risk of ~1%). High risk is when the score is 2 or more (annual stroke risk of >2.2%).

Work out CHA2DS2VASc score for Mr Black…. Score is 2 (diabetes and hypertension).

CHA2DS2VASc risk scoring

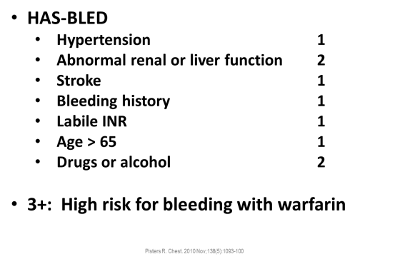

HAS-BLED risk scoring

In addition, as well as reducing the risk of stroke, anticoagulation will also increase the risk of a major bleed. We can use another scoring system to gauge the risk of bleeding (HAS-BLED score). We discuss with the patient the pros and cons of being on anticoagulation versus the risk of getting a stroke if not being on anticoagulation using the above scoring system and clinical assessment.

-

Causes of HFpEF; Treatment of risk factors

The other aspect of management is to treat the underlying causes that may be driving his AF but also increasing his risk of developing a major cardiovascular event (obesity, hypertension and diabetes).

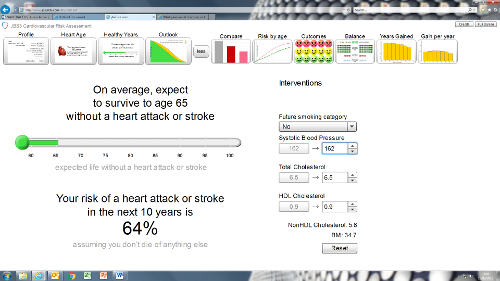

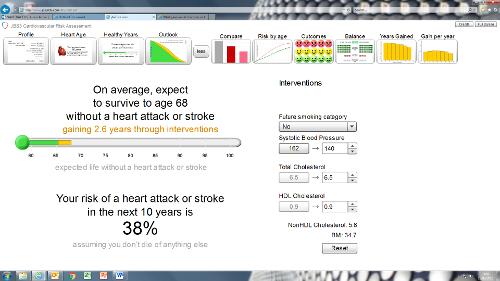

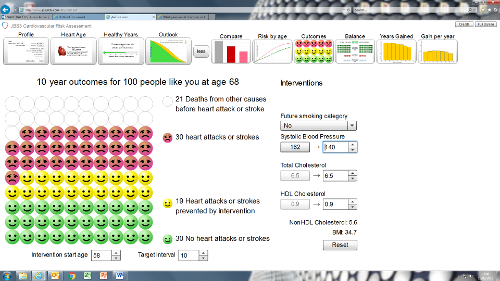

We advise using the JBS3 risk profile assessment as it is easy to do in front of a patient and has a graphical format that the patient can understand which may influence the likelihood of behaviour change.

E.g. worked example for Mr Black: inputting his age, gender, BMI, cholesterol profile, BP, presence of AF, hypertension, CKD etc… risk can be worked out and various parameters altered to show risk reduction. Promote lifestyle changes (Mediterranean diet).

Review of medications:

- Control of diabetes (metformin dose may need to be increased or addition of other antihyperglycaemics)

- Control of hypertension (benefit from RAAS inhibition in diabetic patients with kidney disease e.g. ACE inhibitor)

- More effective lipid control (increasing atorvastatin dose)

-

Natriuretic peptides

Difference between heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and reduced ejection fraction. Heart needs to pump blood round the body. To do this effectively the myocardium needs to both contract (what ejection fraction measures) and relax (not available from ejection fraction). A failure of one or both can cause intraventricular pressure to rise causing symptoms of heart failure.

Pharmacology of NT-proBNP: Natriuretic peptides (ANP and BNP) are released by the stretched atrium into the blood stream. They are a natural diuretic and vasodilator. In AF levels can often be elevated in the mild range (~300 pg/mL). In acute heart failure NT-proBNP levels are often in the thousands. A cleaved product called NT-proBNP is inactive and lasts in the blood for a while which makes it good as a biomarker of heart failure.

Figure X. ANP and BNP are released in response to atrial/ventricular stretch that occurs in heart failure when both LV end diastolic and atrial pressures rise with fluid retention. Both are peptides that have salutatory effects to counter rising pressures (e.g. vasodilatory and natriuretic).

Figure Y. Endopeptidases cleave BNP into inactive components detectable in the blood. This forms the basis of diagnostic tests for heart failure

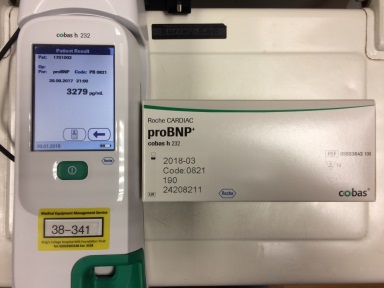

Figure Z. A point of care machine used to rapidly diagnose heart failure. In this case it detects NT-proBNP.