8: Summary

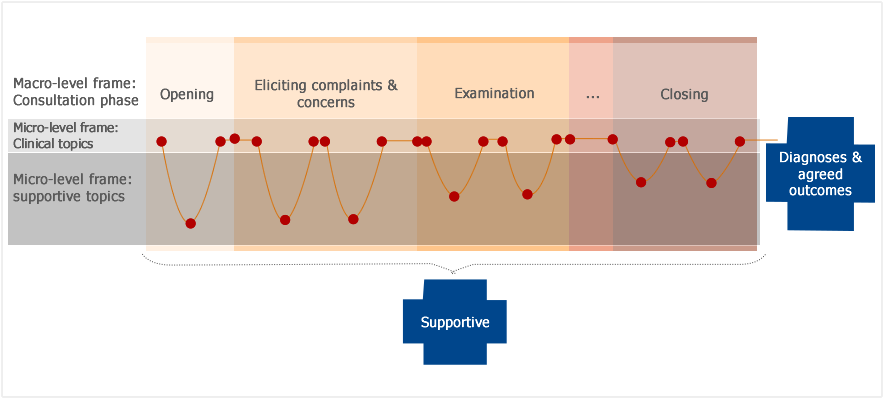

(1) A medical consultation can be seen as a journey that the clinician walks the patient through.

Goals

(2) The ultimate goals of the journey in the given example are diagnosis, agreed outcomes and support for the patient over the consultation process. The goal of support is achieved as the consultation progresses whereas the goals of diagnosis and agreed outcomes are achieved by or at the end of the consultation.

Phases

(3) During this journey, the consultation will go through several phases, such as the opening, eliciting information, examination, explaining/planning and closing. (Silverman et al., 2013, Gill and O'Neill, 2012)(Silverman et al., 2013, Gill and O'Neill, 2012)(Silverman et al., 2013, Gill and O'Neill, 2012).

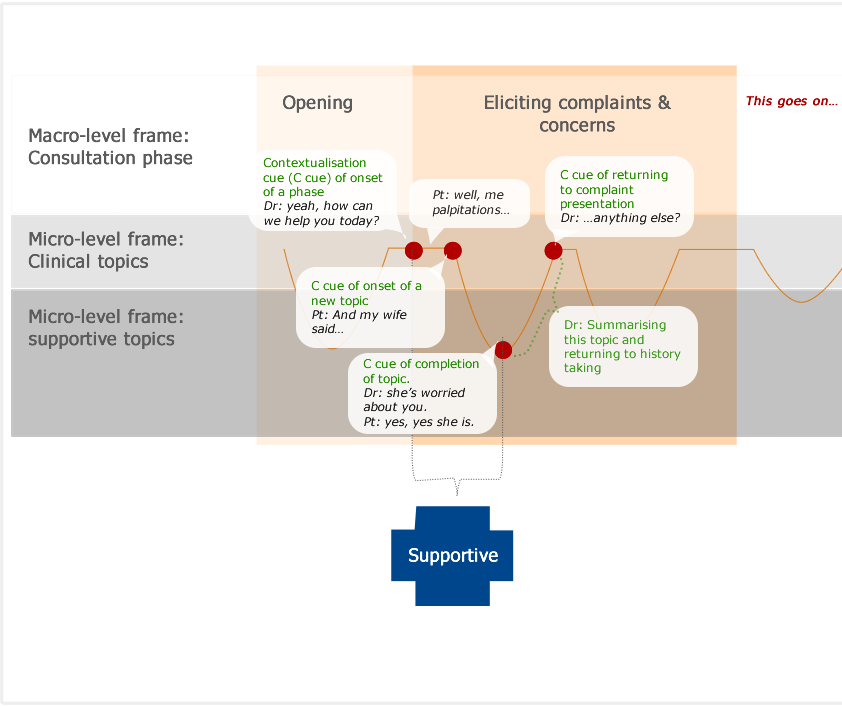

(4) Different phases of the consultation are signalled by the doctor using contextualisation cues (marked with dots) that denote the completion of the previous phase and the onset of a new one. Contextualisation cues often operate at the unconscious level, that is, we are not aware that we are performing them. Contextualisation cues are too numerous to outline or analyse each one in detail; however, cues that denote the beginning, resuming and ending of a phase and the types of topics are worth conscious analysis.

As demonstrated in the sample analysis, these may be marked by summaries, continuers, questions, repetitive structures and so forth. Although these phase frames usually occur in sequence, the sequence may change depending on the situation that the patient and the doctor are dealing with.

Phase frames may also occur more than once in a consultation.

It is the doctor’s responsibility to provide clear contextualisation cues for the patient, sensitively pick up patient’s cues and respond to them (Silverman et al., 2013, Neighbour, 2005). This is key to enabling effective communication.

Topics

(5) Patients’ talk contains two types of broad topics: clinical talk/topics (eg. symptoms, medical history, diagnosis etc.) and supportive talk/topics (eg. emotions, clarity of language, setting structure of a consultation). These topics are intertwined with each other over a consultation so the journey is not straightforward as it may seem to be at first sight. And changes of topics are led by contextualisation cues produced by both the patient and doctor. Both clinical talk and supportive talk are allowable topics within consultations. Supportive talk can become clinically relevant (eg. with distressed patients). Even if supportive talk has little clinical relevance, this does not make it irrelevant to the consultation.

(6) Let’s zoom in and have a closer look at how the doctor and the patient walked from one part of the journey to another by producing and picking up contextualisation cues from each other. We will focus on cues that help speakers to move from one frame to another. You will find more detailed analysis in the demo analysis and the exercises in previous pages.

(7) After greeting, self-introduction with which to establish the initial rapport with the patient, the doctor produces a cue that potentially marks the ending of the ‘opening’ frame and the beginning of ‘eliciting present complaint’ frame, ‘ Yeah, how can we help you today?’ The reason that this is a potential is because if the cue is not recognised by the patient and responds to it accordingly this cue is not evidenced in the interaction. However, here the patient does pick it up and gives a description of his symptoms, ‘Well me palpitations, that’s what I call them anyway, er they haven’t stopped yet, they’ve been going on for at least about 4 hours now ’

(8) Now the doctor and patient stay in the frame of ‘eliciting present complaint’ where the consultation is usually dominated by patient’s historical account of the current complaint, during which the patient throws both clinical cues and psychosocial cues, like in this case. Soon after telling the doctor that he has got palpitations, the patient says, ‘And my wife said to me, look I'm going to get you in the car she said, and I’m gonna get you off to hospital, so a doctor can actually see them while they are actually happening are actually happening to me’ This marks the shift from the clinical talk to the social supportive talk, that is , the shift from the micro-level clinical frame to the micro-level supportive frame (within the macro-level complaint presentation frame). The straight line indicates the clinical talk while the curved line indicate the social frame.

(9) Note how the doctor deals with this social topic. Her talk is minimal during the patient’s talk. But she summarises by the end of it, ‘she’s worried about you.’ This is a very clear cue that demonstrates and communicates an understanding of the patient’s wife’s concerns, which is then confirmed by the patient, ‘yes, yes she is’. Note how the doctor negotiates for the end of the social topic here. She tentatively treats this ‘yes, yes she is’ as an end to the previous topic because the patient does not appear to intend to talk further either. She then produces a summary, focusing on the clinical presentations ‘humm (.) .hh so you’ve had some palpitations, going on for 4 hours today, anything else? (1.6)’. This is a cue to the patient that she intends to move back to the clinical frame; however, it’s open for discussion in case the patient is not ready for it. This summary ending with ‘anything else (1.6)’ is suggestive of a preferred clinical frame but still leaves the conversation open so the patient can also choose to go back to the social frame, which is not the case here. Instead the patient follows the cue and present more symptoms, bringing the conversation back to the clinical frame.

(10) The doctor is strategically using different cues to provide the consultation structure from opening to eliciting present complaint; and to enable or rather empower patient to structure their social talk.

(11) As the complaint presentation goes on, the doctor is summarising and repeating back to the patient, which constitutes cues of attentive listening and intention to stay on the topic.

The following examples illustrate where the doctor is summarising and repeating back to the patient, which constitutes cues of attentive listening and intention to stay on the topic:

“DR: Right, ok so you’ve had this fast, fluttering of your heart or fast heart rate for about 4 hours, you feel anxious or a bit odd with it, anything else at all?”

“DR: Ok what I’d like to do now, is perhaps go over the story a little more, perhaps find out if you’ve had anything similar before, and then ask you some specific questions about some other things that sometimes patients feel along with the palpitations and the chest pain if that’s [alright. [OK?”

“DR: So it was the fact that they weren’t going away for 4 hours that was REAlly:: concerning you and your wife particularly?”

(12) Within the macro eliciting frame there are other sub-clinical frames, such as eliciting initial complaints, taking social history and medical history, etc. We have presented detailed analysis in the demo. You can try to map them in this way. It will help you better understand how the doctor and patient managed their journey and hopefully it will help you develop your own way of doing it.