John Barker

49, Male

Tutorial on: The Jugular Venous Pressure (JVP) and Pulse Contour

-

DEFINITION

Information that can be derived from an assessment of the jugular venous pulse includes determination of the mean central venous pressure, venous pulse contour, and presence and type of cardiac dysrhythmias.

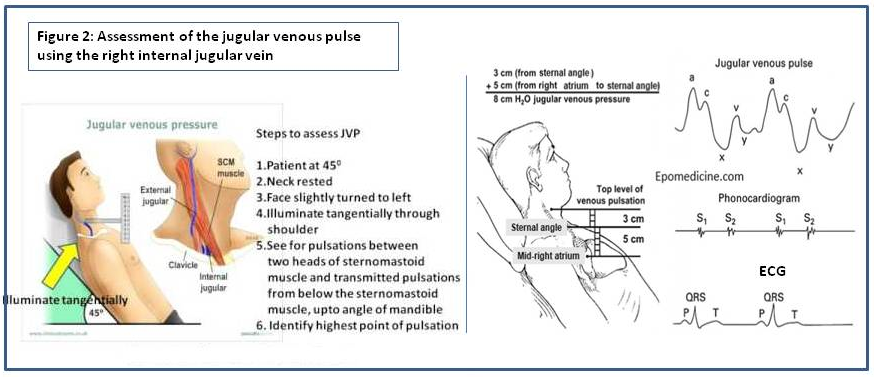

The jugular venous pressure (JVP) is usually assessed by observing the right side of the patient's neck. The normal mean jugular venous pressure, determined as the vertical distance above the midpoint of the right atrium, is 6 to 8 cm H2O. Deviations from this normal range reflect either hypovolemia (i.e., mean central venous pressure less than 5 cm H2O) or impaired cardiac filling (i.e., mean central venous pressure greater than 9 cm H2O). The normal jugular venous pulse contains three positive waves. By convention these are labeled "a," "c", and "v" (Figure 2). These positive deflections occur, respectively, before the carotid upstroke and just after the P wave of the ECG (a wave); simultaneous with the upstroke of the carotid pulse (c wave); and during ventricular systole until the tricuspid valve opens (v wave).

The “a” wave is generated by atrial contraction, which actively fills the right ventricle in end-diastole.

The “c” wave is caused either by transmission of the carotid arterial impulse through the external and internal jugular veins or by the bulging of the tricuspid valve into the right atrium in early systole.

The “v” wave reflects the passive increase in pressure and volume of the right atrium as it fills in late systole and early diastole.

Normally the crests of the a and v waves are approximately equal in amplitude. The descents or troughs of the jugular venous pulse occur between the "a" and "c" wave ("x" descent), between the "c" and "v" wave (" x′ " descent), and between the "v" and "a" wave ("y" descent). The x and x′ descents reflect movement of the lower portion of the right atrium toward the right ventricle during the final phases of ventricular systole. The y descent represents the abrupt termination of the downstroke of the v wave during early diastole after the tricuspid valve opens and the right ventricle begins to fill passively. Normally the y descent is neither as brisk nor as deep as the x descent.

Abnormalities in the jugular venous pulse may be reflected in either the mean pressure, amplitude, or configuration of the positive waves or negative troughs, or in the sequence or absence of the positive waves.

-

BASIC SCIENCE

The anatomic relationships of the right internal and external jugular veins to the right atrium are important to an understanding of the clinical evaluation of the venous pulse. The right internal jugular vein communicates directly with the right atrium via the superior vena cava. There is a functional valve at the junction of the internal jugular vein and the superior vena cava. Usually, however, this valve does not impede the phasic flow of blood to the right atrium. Thus the wave form generated by phasic flow to the right atrium is accurately reflected in the internal jugular vein. The external jugular vein descends from the angle of the mandible to the middle of the clavicle at the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The external jugular vein possesses valves that are occasionally visible. The relatively direct line between the right external and internal jugular veins, as compared to the left external and internal jugular veins, make the right jugular vein the preferred system for assessing the venous pressure and pulse contour.

In determining mean jugular venous pressure, one assumes that the filling pressure of the right atrium and right ventricle mirror that of the left atrium and left ventricle. This relationship is usually correct. Thus, a mean jugular venous pressure greater than 10 cm H2O usually indicates volume overload, while a low jugular venous pressure (i.e., less than 5 cm H2O) usually indicates hypovolemia. But there are important, notable exceptions to this relationship. First, acute left ventricular failure (as may be caused by a myocardial infarction) may significantly raise the pulmonary capillary wedge pressure without raising the mean right atrial and jugular venous pressures. Second, pulmonary hypertension, tricuspid insufficiency, or stenosis may be associated with elevated mean right atrial and jugular venous pressures while leaving the left heart pressures unaffected. In using the mean jugular venous pressure in clinical practice, the physician must correlate this bedside measurement with the other information gained from the history and physical examination.

[ADAPTED FROM: Chapter 19, The Jugular Venous Pressure and Pulse Contour, in Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations,3rd edition. Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Boston: Butterworths; 1990 ]

Figure 2: Assessment of the jugular venous pulse using the right internal jugular vein