History

Important points to be noted include the following:

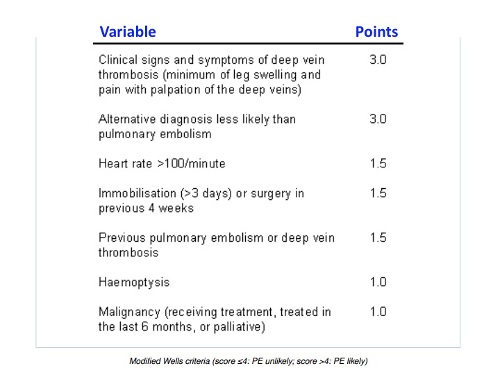

- Symptom onset: can give clues to aetiology. Acute onset of chest pain and shortess of breath indicates MI, pulmonary embolism, or pneumothorax. History should be evaluated for prior DVT and pulmonary embolism. Presence of malignancy or hypercoagulable states increases the risk of pulmonary embolism. The modified Wells criteria should be used for risk stratification.Subacute onset over hours to days suggests infection or inflammatory causes. Chronic pain over weeks may indicate malignancy or TB.

- Radiation of pain: to back, shoulder, arms, or jaw raises suspicion for aortic dissection, or MI.

- Prodromes: viral prodrome, fever, sputum production, and sick contacts suggest an infectious aetiology.

- Drug history: recent initiation of a new drug can cause pleural inflammation.

- Exposures: history of exposure to asbestos should be sought.

- Autoimmune features: suggested by the presence of other signs and symptoms such as malar rash in SLE, joint pain in rheumatoid arthritis, or dry mouth and eyes in Sjogren's syndrome.

Pleuritic Chest Pain -Definition

Pleuritis is defined as inflammation of the pleura. The pleural space, as a thin fluid-filled space between the lung and the thoracic cavity, enables the smooth frictionless movement of the lung during respiration. It is lined by 2 layers of pleura: the visceral (covering the lung) and the parietal (covering the thoracic cage). Pain receptors are present on the parietal pleura. Irritation and inflammation of the pleura presents with symptoms of sharp lancing, fleeting pain in the chest that is exacerbated by deep breathing, coughing, sneezing, or Valsalva (forced expiration against a closed airway) and Mueller manoeuvres (reverse of Valsalva manoeuvre).

It is important to evaluate and exclude potentially life-threatening conditions such as pulmonary embolism, acute coronary syndrome, aortic dissection, and pneumothorax during evaluation. Pneumonia must also be considered. Though not causes of pleuritis per se, conditions such as pericarditis, perforated viscus, and costochondritis should be considered in the differential diagnosis when patients present with chest pain that is pleuritic in nature.

Pathophysiology of Pleuritic Chest Pain

The pleural space is a potential space that can be filled with a variety of substances including transudative fluid, exudative fluid, pus, blood, air, or chyle. The pleural lining consists of a single layer of mesothelial cells supported by connective tissue. This layer not only acts as a mechanical envelope but also serves a biological role. It regulates diffusion of substances into the pleural space and plays an integral role in inflammatory responses to stimuli such as infection, traumatic injury, or introduction of foreign substances such as air, blood, or asbestos. Mesothelial cells recognise invasion of the pleural space and initiate recruitment of cells through co-ordinated expression of cytokines, chemokines, and vascular adhesion molecules. Prompt resolution of the inflammation may allow the pleural surface to return to normal with no sequelae. However, prolonged inflammation will result in distortion of normal structure by fibrosis, adhesions, and scarring. Resolution of inflammation is directed by initiation of neutrophil apoptosis by mesothelial cells.

Pulmonary embolus

A potentially life-threatening condition that can cause sudden death from hypoxaemia, shock, and haemodynamic compromise. Pre-test possibility of pulmonary embolism should be assessed using modified Wells criteria.

D-dimer should be measured using one of the highly sensitive ELISAs for low probability cases. For high probability cases, investigation should proceed directly to CT pulmonary angiogram or V/Q scan. Depending on the clinical condition, anticoagulation, thrombolysis, or rarely thrombectomy should be considered.