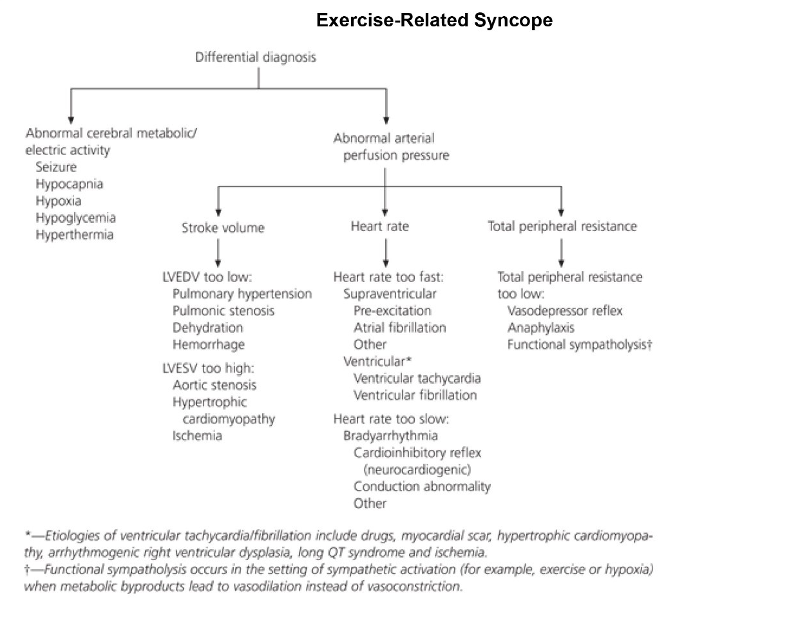

Syncope can be defined as the sudden, transient loss of consciousness due to global cerebral hypoperfusion and is characterized by spontaneous and complete recovery. In contrast, pre-syncope is the presence of light-headedness or dizziness that almost results in loss of consciousness. There are a large number of causes of syncope which can be broadly divided into 2 groups (Figure 1): those associated with abnormal cerebral metabolic and/or electrical activity and those related to abnormal arterial perfusion pressure. Both can occur either in relation to exercise or at rest.

Differential diagnosis of exercise-related syncope in youong athletes. Arterial perfusion pressure is a function of the "triple product" of heart rate x stroke volume x total peripheral resistance. (LVEDV = left ventricular end diastolic volume; LVESV = left ventricular end systolic volume).

SOURCE: Information from Levine BD, Buckley JC, Fritsch JM, Yancy CW Jr, Watenpaugh DE, Snell PG: Physical fitness and cardiovascular regulation mechanisms of orthostatic intolerance. J Appl Phsiol 1991; 70:112-22

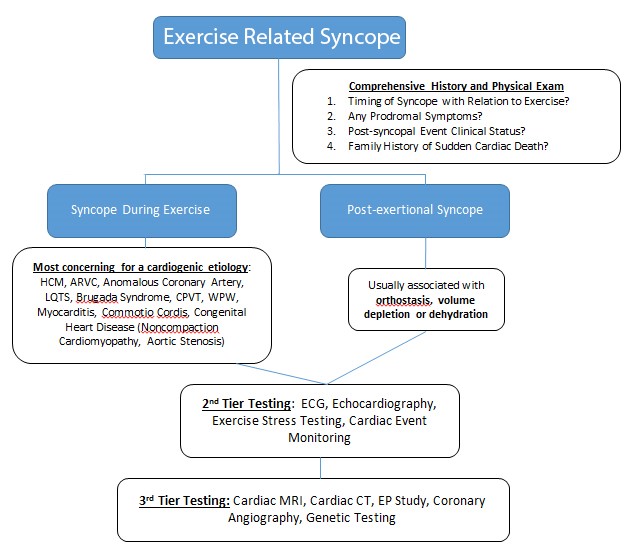

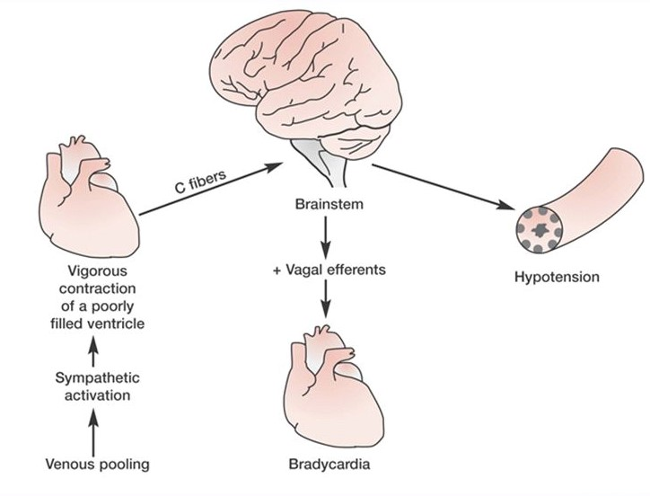

With respect to exercise-related syncope, this can occur either during exercise or directly after exercise (post-exertional syncope) (Figure 2). Post-exertional syncope is relatively common, often benign and has a favourable long-term prognosis. It usually occurs when exercise is stopped suddenly, resulting in loss of lower limb muscle pumping function (which is crucial to maintaining cardiac output during exercise), subsequent reduction of venous return to the heart, and diminished cardiac output. At the same time, circulating catecholamines and forceful ventricular contractions against a reduced ventricular volume stimulate ventricular mechanoreceptors leading to activation of the Bezold-Jarisch cardiac depressor reflex through vagal afferent c-fibres carried to the brainstem (Figure 3). This reflex results in paradoxical bradycardia, acute loss of postural tone and hypotension through activation of vagal efferent fibres, and eventually global cerebral hypoperfusion through reduction in blood pressure. The dehydration and reduction in plasma volume that often accompany exercise contribute to this. Other factors in an athletic individual that may contribute to post-exertional syncope are higher levels of resting vagal tone, which sensitize the efferent limb of the Bezold-Jarisch reflex, and orthostatic intolerance resulting from hemodynamic changes that are usually beneficial during training. This type of syncope is sometimes also called “neurocardiogenic” syncope.

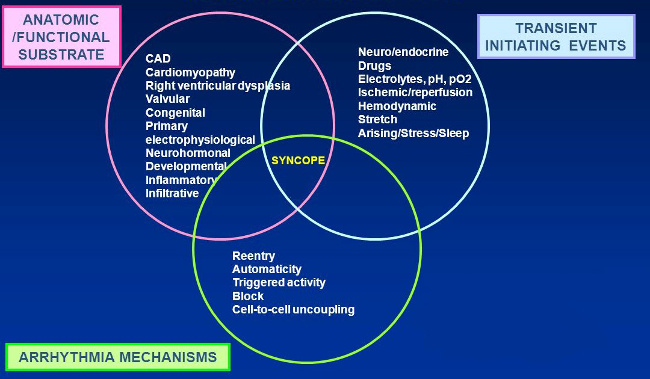

In contrast, syncope that occurs during (i.e. in the middle of) exercise is an ominous symptom and should always raise concern for structural and/or electrical cardiac disease. Indeed, it may be the only symptom that precedes sudden cardiac death (SCD) in a young individual with an inherited or congenital cardiac condition. There are a number of cardiac conditions which can cause exertional syncope (Figure 2); however, the mechanism of syncope is usually either a sinister ventricular arrhythmia, mechanical obstruction to blood flow out of the heart, or a combination of the two. More rarely in young (aged <35 years) individuals but more commonly in older cohorts, cardiac ischaemia may be a third mechanism. Environmental factors may contribute to and exacerbate this process (Figure 4).